Tranalysis

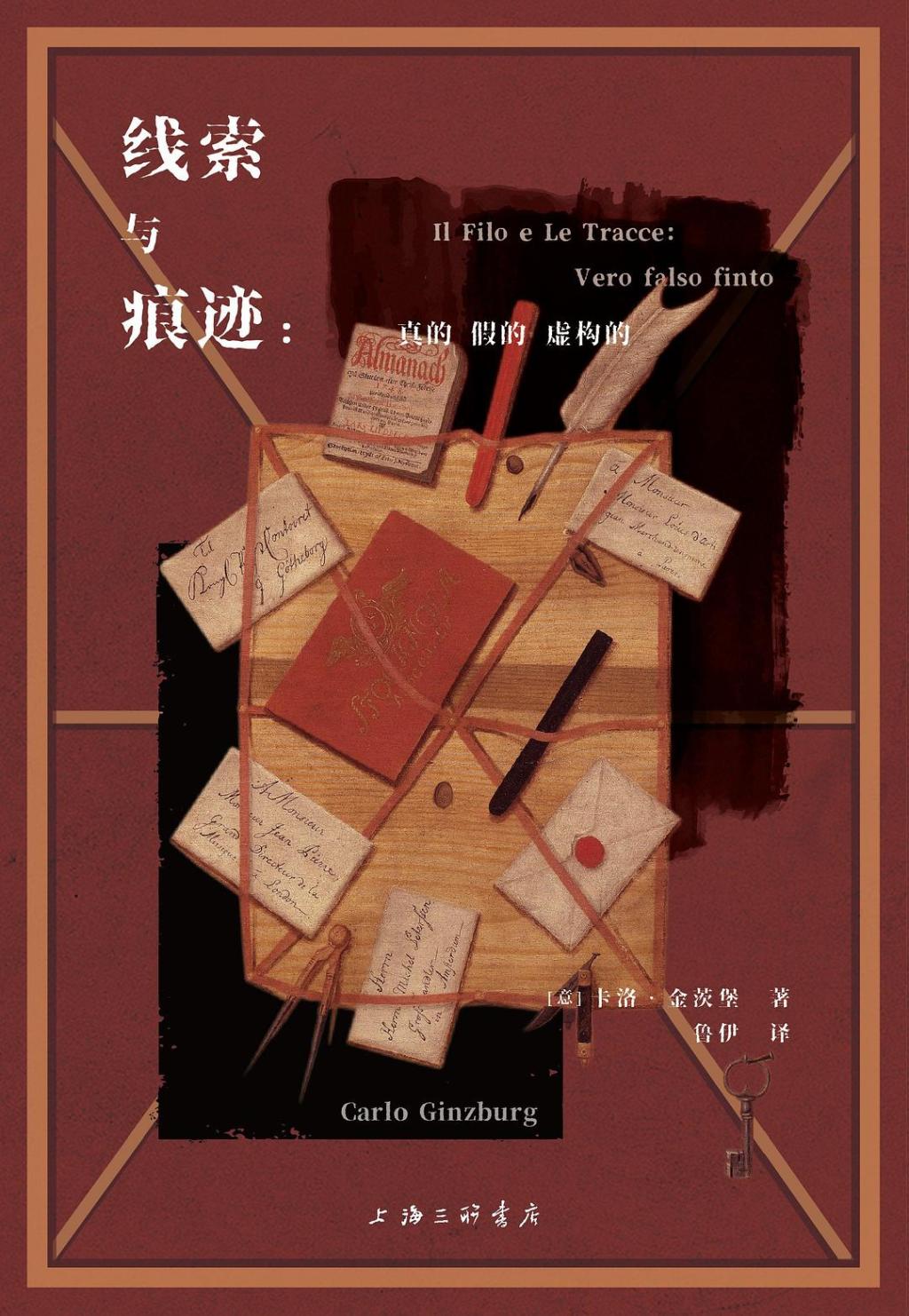

\Clues and Traces: Real, Fake, Fictional\ by Carlo Ginzburg, translated by Rui, published by Shanghai Sanlian Bookstore in March 2025, 478 pages, 118.00 yuan.

Even professional historians who have not read Carlo Ginzburg's previous works, especially \The Cheese and the Worms\ and \The Night Battles,\ will find it quite challenging to directly engage with his new collection, \Clues and Traces.\ It is hard to imagine an elderly scholar adopting an energetic frog leaping tactic within his vast and scattered knowledge network, only to launch an attack on the topic after repeated detours. For the average reader, the experience of reading this book is probably similar to watching a sports program they are not familiar with; you cannot judge which rock a rock climbing expert will choose to leverage, and you might either watch with curiosity or turn off the TV out of sheer boredom.

Thus, writing a comprehensive review of this book is also difficult, as it is hard to know where to start. Taking Chapter 8, \In Search of Isra?l Bertuccio,\ as an example, the initial paragraphs on Hobsbawm's analysis might lead you to believe that he is going to explain the transformation of historical research, but he suddenly stops, introducing a historical figure named Bertuccio through the character Julien in the literary work \The Red and the Black.\ After leaving this name to the reader, he begins to discuss the various versions of the true protagonist, Marino Faliero, including how Byron's version contains certain allusions, and how he selects and uses historical materials. The author then proceeds to investigate Bertuccio's name and identity, continuing to explore the differences between fiction and historical truth, and finally concludes that in the continuous changes of context, the identities of characters and the details of events must be corrected, and the historical images passed down through the ages also dissipate and decompose. (Page 237) Here, Hobsbawm's concern is finally addressed: the belief that historical research can distinguish between fact and imagination, the possible and the unverifiable, what actually happened and what we want to happen through evidence and universally accepted logical rules has been fundamentally shaken.

It may sound somewhat nihilistic, but this \Ship of Theseus\ is indeed a dilemma commonly encountered by historians—if we liken a historical event to a ship, with time, place, and characters as its components, is the ship still the same one after we replace the problematic parts? Ginzburg, who focuses on microhistory, feels this more deeply because he frequently witnesses how the corruption of details can lead to diverse analytical outcomes, blurring the line between historical narratives and fictional ones. But the master is, after all, a master; he does not fall into various skeptical positions because of this, but instead poses a constructive question: any narrative—whether true, false, or fictional—implies some kind of relationship with reality.

Carlo Ginzburg

One, the matter at hand and historical narrative

To find a suitable thread in Ginzburg's bizarre world of thought, let's start with Chapter 11 of this book, \The Lonely Witness: The Extermination of Jews and the Principle of Authenticity.\ The logical notion that \a single witness does not stand\ is engraved in the minds of every historian like a steel seal, and its correctness is beyond doubt, but Ginzburg偏偏不信这个邪. He first illustrates that孤证不为证(testis unus,testis nullus)originates from a common principle in Roman and Jewish legal traditions, which refuses to recognize the legitimacy of a single testimony in a trial. Next, the author keenly points out that although the promotion of this principle in historiography is unquestionable, if important historical documents are strictly processed according to this standard, many real events will vanish due to \孤证\; on the contrary, dealing with historical events with a seemingly rigorous positivist attitude will also lead to bad consequences, such as the Holocaust denial by scholars like Faurisson, which is morally and politically repulsive, yet difficult to refute within a rigid empirical logical system.

The so-called real events here refer to Croce's \cosa in sé,\ which have indeed occurred in history, but of which we are unaware. A relevant document is a fact, the doer is a fact, the narrator is a fact, and every testimony is actually a witness to itself – witnessing its own moment, witnessing its own origin, witnessing its own intent, and nothing more. Therefore, any document, no matter how much it belongs to direct materials, or primary materials, still maintains a relationship full of questions with the truth (\cosa in sé\

Using a well-known Chinese historical event as an example, let's first assume a \fact\: In August of the third year of the reign of the Second Emperor of Qin, Zhao Gao established his authority through communication with his court officials during a court meeting, but the specific methods and means he used are unclear to us. The most authoritative document, \Records of the Grand Historian - Biography of the First Emperor of Qin,\ provides the following historical narrative:

Zhao Gao wanted to create chaos, but he was afraid that the court officials would not obey him. So he first set up a test, holding a deer and presenting it to the Second Emperor, saying, \It's a horse.\ The Second Emperor laughed and said, \Has the Chancellor made a mistake? Calling a deer a horse.\ He asked his attendants, and some were silent, while others agreed it was a horse to flatter Zhao Gao. Those who said it was a deer, Gao secretly punished them according to the law. After that, all the court officials were afraid of Gao.

The story of \calling a deer a horse\ has been regarded as historical fact by later generations, but it is not easy for posterity to accept the rationality of this situation. Not to mention how a wild animal could remain quiet and not make a fuss in a court full of officials, just imagining the ministers arguing over this is extremely absurd. The Japanese scholar Miyazaki Ichisada believed that this story is an excellent comedy, but it is difficult to take it directly as historical fact. Sima Qian depicted it so vividly because he referred to some written materials, such as the popular puppet plays of the Han Dynasty. Actors in pairs, sometimes dancing and sometimes discussing, performed famous historical events. These plays were often performed in the court and in the markets where people gathered, so they had a wide dissemination range. It is very likely that their scripts entered into Sima Qian's selection of materials.

A historical narrative can be very much like a fictional narrative, with countless examples to illustrate this point. Ginzburg is more interested in why we take the events described in a historical work as true, after all, there is no difference in appearance between a false statement, a true statement, and a fictional statement. Therefore, he analyzes the two routines of historical narratives to find the elements that guarantee authenticity.

Two, Vivid Description and Vulgarity

The term \vivid description\ (enargeia) specifically refers to the orator's provision of comprehensive information to move and persuade the public, in order to disseminate the truth he states. Ginzburg uses it to describe the style of Homer's works - vividness is the purpose of description, and authenticity is the effect brought about by vividness. For example, in a passage describing a battle scene in the \Iliad\:

On the ground, swift Achilles continued to chase Hector without letup, like a hound in the mountains pursuing a fawn that has leaped from its nest, relentlessly crossing ridges and ravines. Though the fawn hides beneath the bushes, curling up its form, the hound dashes over to sniff out its trail, and then springs up to pursue it—just so, Hector could not escape the son of Peleus with his mighty strides.

Setting aside the fictional nature of mythological figures and stories, Homer's writing is clearly a form of direct witnessing (autopsian) and presence (parousian), vividly bringing a chase scene to life before the reader's eyes. Historians, when confronted with such texts, may momentarily feel as if Homer was on the walls of Priam's city, witnessing it all, but reason quickly denies this, leading to an awareness that our knowledge of the past consists only of fragmented pieces. When these intermittent histories are strung together into stories, they will inevitably be filled with a great deal of imagination. Based on this, the sixteenth-century philologist and antiquarian Robortello pointed out that the methodological elements of history belong to the same category as rhetoric, rhetoric being the mother of history.

The controversy sparked by this method of historical writing continues to this day, such as the writing of contemporary Sinologist Jonathan Spence, which has always been subject to questioning. In his work \The Death of Wang,\ the historical material he mainly uses, \Tancheng County Annals,\ can still be considered a reliable history, while the county official's memoir \Fu Hui Quan Shu\ contains many absurdities, and the citation of the pure literary work \Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio\ has caused widespread controversy in academia. Spence explained, \Pu Songling lived in the era involved in this book, although it is a novel, it represents a point of view... My task is to be a fact catcher, to search for those definite pieces of the puzzle.\ With these \unreliable\ historical materials as support, Spence's depiction of an ordinary woman in a marginal county of Qing Dynasty China in the seventeenth century reached a meticulous level, writing that she wore a pair of old sleeping shoes with red cloth soft soles, her inner shirt was blue, and her thin underwear was white; writing that when she was strangled by her husband, her legs twitched so hard that they crushed the mat and stepped through the straw mat underneath. This is fictional because Spence was not on the scene; this is also real, this vivid description truly recreates the mental dilemmas and tragic fate faced by ordinary women like Wang at that time in society.

In Chapter 3 of \Clues and Traces,\ Ginzburg summarizes another opposite historical writing technique and, borrowing from the grammarian Gellius, names it \subrustice,\ a plain and unadorned style aimed at breaking classical structures. Starting from Montaigne's \On Cannibals,\ Ginzburg points out its deliberately casual writing style is closely related to the rough and natural popular taste of the 1530s, and further analyzes Montaigne's reflection on civilization and barbarism—\ people are considered barbaric by us precisely because they have not been shaped by human cunning and remain close to their simple origins.\ Recognizing distance and diversity, Montaigne strives to understand the customs of others and shifts perspectives, thus discovering another possibility for writing history. In Gombrich's words, taste is a filter that not only has moral and cognitive consequences but also aesthetic impacts. What Ginzburg wants to say is that, claiming civilization and starting with the thoughts and concepts of contemporary society, one will inevitably examine history with arrogant prejudice.

Three, the technique of reflection and the alienation effect.

In Chapter 6, when analyzing Auerbach's interpretation of Voltaire, Ginzburg reminds readers to pay attention to two artistic techniques, Voltaire's Scheinwerfertechnik and Brecht's Verfremdung-Effekt, both of which are extremely similar in creating the effect of \defamiliarization.\ \Defamiliarization,\ proposed by Russian formalist Shklovsky, is the process of changing habitual perception and descriptive methods to allow the aesthetic subject to gain new cognition. For example, turning a daily object into a sacred artifact or, conversely, describing a sacred event as mundane. Take, for instance, soldiers beating drums on the battlefield; writers usually depict this scene with great passion, but in Voltaire's writing, it is merely \bloodthirsty madmen dressed in red and wearing hats two feet tall,\ \holding two little sticks, striking the taut donkey skin to make noise.\

A pure historian would not care about these literary issues, but as a polymath, Ginzburg keenly discovered that a close observation of the function of alienation in Voltaire's works would reveal a more complex story. This master of the Enlightenment used alienation extensively in his works to mock different religions and beliefs, as well as the French society of his time, reflecting his approval of freedom of thought and trade. However, this detached perspective could not exempt Voltaire's views on racial issues from the limitations of his era. Imagine a traveler from space viewing humans as a kind of animal: \Some are superior to blacks, just as blacks are superior to monkeys, and monkeys are superior to oysters\ (page 165). For Voltaire, human history developed within the framework of a hierarchical system, and the slave trade was also a reasonable commercial trade, with the cruelty and injustice being merely a matter of human perception. By closely reading Erich Offenbach's interpretation of Voltaire, Ginzburg magically found the intersection of Enlightenment and Nazism—\intolerance and tolerance led to the same consequence in opposite ways.\

In the discussion of Stendhal in Chapter 9, Ginzburg once again refers to Offenbach and his work \On Imitation\ and reminds readers that the subtitle of this book is called \The Representation of Reality in Western Literature.\ Offenbach's main idea is that the development of history usually generates multiple paths to truth. What is meant by \representation of reality\ is not what historians strive for, the \reconstruction of historical scenes\? The difference is that historians often discard short-term, accidental, and special information in search of the laws of historical development, while in Offenbach's view, through an unexpected event, an ordinary life, or a randomly selected segment, we can achieve a deeper understanding of the overall picture. (Page 243) In other words, with the help of some fictional characters and stories, there is also an opportunity to reach a deeper historical truth. There are probably few people with this concept in the serious historical field, but there are many like-minded individuals in the literary world. For example, for Calvino, even fairy tales are true (le fiabe sono vere), and the reason stories are true is that they simply and repeatedly affirm the truth of humanity— the fate of beauty and ugliness, fear and hope, chance and disaster.

Perhaps some may argue that literature seeks beauty while history seeks truth, and historians should never rely on shaky historical materials to construct history. However, to be fair, isn't our historical research today also filled with \alienation\ techniques? Especially in the study of modern and contemporary history, faced with an ocean of historical materials and historical events that have almost become established views, scholars are almost impossible to make subversive research results, and can only change perspectives in details or use new techniques such as \emotional history\ and \conceptual history\ to \defamiliarize\ the familiar history, brewing old wine in new bottles with similar flavors. Even a somersault of eighty thousand miles cannot escape the palm of Buddha, this increasingly standardized way of working seems to be a re-creation, but it is actually influenced by both past texts and individual tastes, which is the \historical truth perceived by modern consciousness\ that Offenbach opposed.

IV. Ignorance and Delusion vs. Clear and Enlightened Insight

Historians once held a belief that, with the help of evidence and universally accepted logical rules, historical research could distinguish between fact and imagination, between the possible and the unverifiable, and between what actually happened and what we would like to have happened. (p. 218) Today, this belief has been shaken, and historiography can never reconstruct the complete past, thus returning to the core question raised in the first chapter: Is the past represented through rhetorical skills (including fiction) trustworthy? Ginzburg discusses this possibility in Chapter 7 of this book with Barthelemy's work. Barthelemy invented a young man named Anacharsis traveling to Greece, where he attended many banquets, met a series of celebrities, and observed the local customs and habits. This is a travelogue, but not a history, because it is filled with \minor details that historians are not allowed to cite\:

Her dressing table first caught my attention. I saw silver basins and silver pots, mirrors of different materials, hairpins for fixing hair buns, curling irons for hair, hairbands of varying widths, hairnets for gathering hair, yellow hair dye, various bracelets and earrings, boxes of lipstick and lead powder, and kohl for dyeing eyelashes, as well as everything needed to keep teeth clean.

This kind of so-called enumeration is trivial and meaningless in the eyes of historians. Anaxagoras, as a character in the text, is short-sighted, so the information he provides is a kind of \ignorant prejudice\ (sguardo interrogativo) with little value for use; but behind it is the ancient artifacts researcher Barthelemy, who is familiar with the history of Greece in the 4th century BC. His knowledge ensures that the parts about religious ceremonies, festival celebrations, and customs in \The Travels of Young Anacharsis in Greece\ can be called \conscious insight\ (sguardo consapevole). Therefore, although this book cannot be considered a systematic ancient artifacts research paper, nor a historical narrative, it can still provide considerable authenticity. Similar to non-typical historical narratives such as \The Customs\ and \Letters from Athenians,\ the value of this writing lies in \their vivid depiction of the actions and words of Greeks and Persians, allowing us to better understand their customs and habits, far surpassing the long-winded lectures of serious ancient artifacts researchers\ (page 211).

The blending of reality and fiction has always challenged the boundaries of existing historical writing. Ginzburg's case is to piece together reality with fiction, and a more common practice is to weave real elements into fictional works. British writer Byatt, in \On History and Story,\ detailed this interest with John Fowles' novel \The Maggot.\ The historical background of this work is during the reign of King George II, in which the \Gentleman's Magazine\ of 1736 is reproduced month by month.Gentleman's MagazineThe setting aims to evoke a \historical chronology\ and incorporates many real events, including long-forgotten historical fragments such as bone setters, gamekeepers, hangings, and highwaymen, but the author has no intention of creating a historical novel. Instead, the author hopes to recreate the \distant 18th-century past's feeling and tone.\ The effect of this literary work is similar to that of \Cheese and Maggots\ - allowing modern people to truly see the nameless, deceased figures wandering through their already desolate world. Are their stories part of history? More and more people are affirming this, even if these figures are insignificant, they also come from what Fielding called \the grand and true book of nature.\

By the twentieth century, writers became increasingly dissatisfied with confining historical literary works to major events and the powerful, instead using rhetoric and intellect to restore the appearance and voice of history as much as possible, pursuing \impossible precision\ (On History and Story, p. 121). The historical community also began to sing a counter-tune to Braudel and the Annales School in the second half of the twentieth century, with French New History, historical anthropology, and Ginzburg's microhistory research all adopting anti-essentialist and anti-foundationalist attitudes. Ginzburg's attitude is quite moderate; he does not negate grand narratives with the reliability of the micro, proposing to pay attention to themes that have already established their importance, even those considered taken for granted, as well as to previously neglected or belittled research areas, such as local history themes (p. 395). We can also understand Ginzburg's microhistory thought as the intercommunication between \ignorant misconceptions\ and \clear insights\ - when we magnify the scale of observation, we do not see a continuous scene but merely a frame of the historical picture; and by stringing together these gossamer clues with hypotheses, doubts, and uncertain motives, we find that \what is\ does not equal historical documents but exists in the relationship with the series of events before and after.

Overall, Ginzburg advocates microhistory and \clue-based research\ (indizio), opposing the long-standing over-reliance on archival sources and the inherent notions that arise from it: the more authoritative the sources, the better; the more complete, the better; the more diverse, the better. He demonstrates with numerous solid case analyses a danger that, due to the distortion of historical writing and the pollution of discourse power, macrohistory, which attempts to explain everything, obscures the true face of history. And those subtle, fragmented, and traditionally neglected materials, whether real, fake, or fictional, all provide us with the possibility of reconstructing historical facts. He reminds us that the value of sources lies not in commonality but in their unique \specificity,\ and exploring those trivial details helps us touch the capillaries of history, feeling the rough and warm cultural folds.