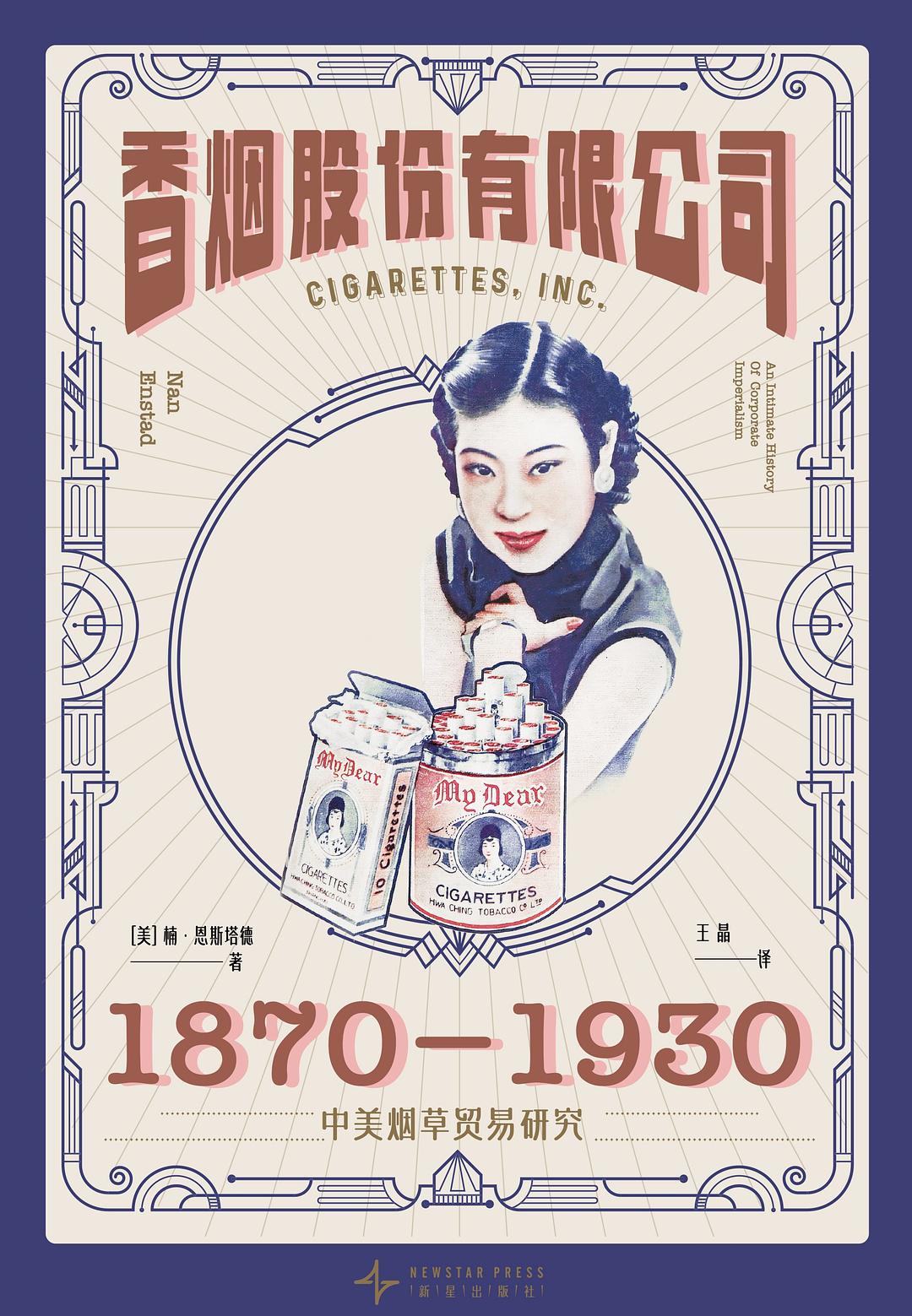

Tranalysis

Two narrative myths

In 1916, Lee Parker left his father's tobacco farm in Ahoskie, North Carolina, and came to Shanghai, China. Sixty years later, he wrote in his memoirs: "I had just arrived from the United States and was employed by British American Tobacco, responsible for 'putting a cigarette in the mouth of every China man and woman.' Parker's father sent him to Wake Forest College, hoping that he would become one of the few white professional class after graduation. But even with a college degree,"it was difficult for rural people to find work," Parker recalled. He heard that there was a tobacco market buyer in Wilson City who was recruiting young people for his China branch, so he borrowed five dollars from his brother and went to Wilson. Parker accepted a "half-minute to two-minute" interview on the spot at the tobacco warehouse. After that, his life path suddenly turned east, China, becoming the world's first cigarette salesman for a multinational company.

Parker was one of hundreds of young white men who came to work at British American Tobacco's China branch from tobacco growing Virginia and North Carolina from 1905 to 1937. It was during this period that cigarette consumption around the world rose sharply. Southerners occupy management positions in every department of the company. Richard Henry Gregory from Granville County, North Carolina, runs the agricultural department through which Southerners introduced bright leaf tobacco and curing systems to China farmers.

In the 1920s, Ivy Riddick from Raleigh, North Carolina, managed a large cigarette factory in Shanghai, a period when major strikes and anti-imperialist protests broke out. James N. Joyner Joyner was born in Goldsboro, North Carolina, and worked in sales in China from 1912 to 1935. He was the head of two major sales departments. During the years of rapid expansion of British American Tobacco's China branch, James A. Thomas of Reidsville, North Carolina. Thomas) is the "top leader" in charge of China business. Behind each manager stand dozens of ordinary employees, most of whom are white southerners from rural areas who work for the China branch for one contract period (4 years) or multiple contract periods; during its operations, hundreds of southerners came to China.

These people are part of a huge network that selects white men from the bright leaf tobacco areas of the North by South and puts them into start-ups in the United States and China. Their fathers, brothers and cousins stayed in the United States, working in similar jobs at the local tobacco company that was also emerging. To be a member of this transnational network, one must be a white male and have some connection to the growing, curing, auctioning or production of bright leaf tobacco. What matters is not what the person knows, but who he knows, because for someone with relatives working in the tobacco trade, even if he has no special training or experience, he can still enter the industry. This network serves as a management system that coordinates the hiring and placement of white-collar managers in the United States and China; like boards of directors, it forms the structural cornerstone of multinational tobacco companies and, more importantly, even affects day-to-day decision-making and corporate culture.

Until then, we had not heard of the experiences of those who came to China through the Bright Leaf Tobacco Network, in part because these southern rural people seemed unlikely to be global capitalists. Most of them had never left their hometowns before embarking on a long trip to China. For most people from rural areas, Shanghai is the most modern and international place they have ever seen. Generally speaking, they have no higher education. Only a few, like Parker, graduated from Wake Forest College in Winston-Salem or Trinity College in Durham, while others dropped out early and started working, as James A. Thomas did when he was 10. Of course they don't smoke. Especially before the 1920s, cigarettes were the exclusive preserve of the old oilmen in the city; southerners chewed their own tobacco. In the evening, it is very pleasant to hold a pipe in your mouth; in business, smoking a cigar is half the success; but cigarettes are not so popular. In China, men in the Bright Leaf Tobacco Network became the first to surrender to cigarettes. The "deal" was almost easy because they could get cigarettes for free from the company. In the view of some contemporary readers who habitually believe that rural life, especially in the apartheid south, is isolated and intolerant, these people working internationally in the Bright Leaf Tobacco Network may be somewhat different. However, despite their geographical and cultural distance from the financial metropolis of New York, they became representatives of the world's first multinational companies, which in turn promoted the development of cigarettes, a commodity closely linked to modernity.

Only by thinking about how this network arranges employees at all levels can we understand how cigarette brands containing bright leaf tobacco have risen rapidly in the United States and China at the same time. In the 1920s, China consumers favored Ruby Queen cigarettes, made from 100% bright leaf tobacco, and sales reached unprecedented levels; in the United States, sales of Camel cigarettes, made from bright leaf tobacco, soared, far ahead of competitors. By capturing these two huge markets, Camel and Queen have become the two most popular cigarette brands in the world, and it is no exaggeration to say that they have also changed the world. After these achievements, tobacco companies have moved to the forefront of branding, trying new methods to gain the favor of consumers and make them willing to pay for it. Everywhere in the world, cigarettes have become a visual representative of "modern" urban life, and because of their important role in personal and group social interactions, cigarettes have also become a symbolic social product in various personnel disputes and disputes. Companies cannot achieve this feat simply by exporting an American cigarette to China. Instead, this historical narrative of cigarettes is the result of cross-cultural exchanges between the two countries, as innovation and production occur in daily corporate activities.

Camel cigarette advertisement

Bright leaf tobacco cigarettes themselves play a pivotal role in tobacco history, but they are also an accessory in the profound development of corporate empowerment. The U.S. tobacco industry started out as a business partnership rather than a company, but as corporate power shifted more and more, new business practices became possible, and the tobacco industry was able to merge and expand. The loose new company law, the Fourteenth Amendment, the growing importance of stock markets, and corporate groups 'readiness for expansion have all created space for new development potential; tobacco companies are racing to turn these potential into profit and prestige. In fact, the tobacco industry entered the international market at the beginning of the industry's formation, long before it operated as a company. Lewis Ginter from Richmond, Virginia, pioneered success in London with his bright leaf tobacco cigarettes. The owners of the five American tobacco giants have a cooperative relationship with each other, and they understand that the future hope of the tobacco industry lies in foreign markets. Later, they jointly formed the American Tobacco Company (ATC) in New Jersey to gain transoceanic control of the Bonsack cigarette machine, the highest production capacity at the time.

However, after the founding of American Tobacco, one of the founding members, James B. Duke, Duke) seized control of American Tobacco from Kinter and implemented a radical expansion plan. After intense competition, American Tobacco quickly annexed hundreds of companies that dealt in chewing and pipe tobacco. As a result, American tobacco companies have almost complete control of the supply of bright leaf tobacco. Such business practices may even face court charges, but New Jersey's company law and the Fourteenth Amendment protect private property and due process, and the company successfully circumvented government supervision.

American Tobacco also immediately implemented an ambitious overseas expansion plan. After raising some funds through the stock market, the company acquired tobacco companies in Germany, Australia and Japan, and merged with the Imperial Tobacco Company of Britain in 1902 to form the British American Tobacco Company (BAT). American Tobacco and Imperial Tobacco agreed not to set foot in each other's domestic markets, but merged their overseas assets, making British American Tobacco a multinational company fully committed to overseas expansion. American Tobacco owns 60% of British American Tobacco, and James B. Duke serves as chairman of the board of directors of both companies. The overseas expansion of American Tobacco and later British American Tobacco became part of the history of Anglo-American imperialism, which used imperial power to win privileges for foreign companies and assumed the role of extracting profits and forcing manipulation. British American Tobacco's tentacles quickly spread to all parts of the world, and China became its largest trading base overseas.

The Bright Leaf Tobacco Network is an indispensable part of corporate expansion, guiding and managing the on-site construction of large agricultural and factory systems in China and the United States with vastly different geographical conditions. In addition to selecting certain white-collar employees based on race, gender and region, this transnational network also serves as a channel for the circulation of bright leaf tobacco, cigarettes, bright leaf tobacco seeds and related management knowledge. This management knowledge is inevitably mixed with racial discrimination originating in the southern United States. Moreover, although this network is part of the corporate structure, it still plays a key role in the overseas landing of the US and British corporate empires. The best understanding of a corporate empire is that it is not just an occupying or ruling power. It also contains "a hierarchical network of migration, information, power, and rules, made up of workers, immigrants, and managers moving around the world." Based on this definition, we can think that the Bright Leaf Tobacco Network is a manifestation of corporate imperialism that has had a huge impact on both China and the United States.

Corporate empowerment is achieved through daily innovation and transactions among countless people; in turn, cigarettes 'transnational success also benefits from these efforts. In day-to-day business practice, corporate power is inseparable from the emergence of apartheid and imperialism, a relationship that determined the United States 'place in the global order of the 20th century. The Bright Leaf Tobacco Network played a crucial role when I was doing this book's research because it connected the United States and China. Members of management are also members of this network, and they rely entirely on the company's employees, including China entrepreneurs, managers, salespeople, factory workers, farmers and servants, as well as employees including African Americans, white farmers and factory workers, and African-American servants, who are also the founders of the company. As social organizations, the internal situations of American and China cigarette companies are very complex. People's daily contacts must transcend racial differences, otherwise the production and sales of cigarettes will be impossible.

Until now, this history remains unknown because we are deeply involved in the myth of capitalism. There are two interrelated narratives about the tobacco industry that have been repeated on many platforms for decades and seem to be common sense. The first stems from the worship of entrepreneurs. This narrative holds that James B. Duke had an outstanding entrepreneurial spirit that allowed him to control the industry from the beginning. While his competitors were making hand-rolled cigarettes, Duke introduced more efficient machines to make cigarettes, reducing costs and making profits, thereby standing out and forcing his competitors to merge with him to form American Tobacco. This narrative largely attributes this success to Duke's pretentious and risk-taking personality, who refused to play by the established rules of the game and followed his superior business vision.

The second historical narrative is related to the theme of modernity, arguing that advanced technology has shaped the unified pattern of the spread of modern commercial forms and goods from west to east, such as the relationship between cigarette machines and large companies and cigarettes. People's assessments of this process vary: one sees it as a good move to spread advanced things, and another sees it as a violent expansion of corporate empires. Whether praising or criticizing, supporters of this narrative agree that Western tobacco company representatives developed new technologies and products at home, pioneered new forms of business, and then expanded to export them around the world, where they transformed more "compliant" and more "primitive"(or "underdeveloped") societies.

I call these two narratives myths because they are heroic stories that have no historical basis. They are a set of capitalist theories that clearly ignore facts and conceal the history of cigarettes. James B. Duke and the tobacco companies do have a lot of influence, but how we express that influence can change the world. If we want to interpret the history of tobacco companies in a new narrative way, we must look at the innovation and expansion of capitalism from a new perspective.

Reflecting on innovation

In the grand narrative, James B. Duke has become a respected model-a talented and innovative entrepreneur. His legend of reorganizing the cigarette industry with cigarette machines is a textbook example of the economist Joseph Schumpeter's theory of creative destruction. This theory emerged strongly again in the early 21st century. In the decades before and after World War II, Schumpeter discovered an innovation model in which entrepreneurs disrupted existing business practices by using new technologies to create cheaper, lower-quality products. Later, the innovator lowered product prices, catching late-knowing competitors off guard and reorganizing the industry around a new model of success.

Schumpeter himself called on scholars to continue to look for examples of this pattern in historical facts. In the 1960s, researchers began to regard Duke as a typical representative of a creative destroyer, but were sloppy about the actual historical record. The famous business historian Alfred D. Chandler Jr. Dr. Chandler expressed this view in his classic book "The Visible Hand": Historians never examine historical facts. Since then, this short narrative has appeared in almost every history about tobacco or cigarettes, whether it is criticism or praise. This myth has spread from business magazines to popular magazines and website front pages, from business schools to high school, and has even been included in advance history courses in American universities. In other words, Duke's narrative of inventing the cigarette machine shapes the general view of how capitalism works.

The problem is that this narrative is actually wrong. Duke has no particular innovation in cigarettes and machines. In fact, some of Duke's innovations emerged even before his family company started making cigarettes. Cigarette machines are indeed important, but they can be used by all major manufacturers. The key lies in the control of machines in overseas markets. Through the merger, the major cigarette maker has tightened its grip on Bonsack Machinery, which has threatened to award overseas patents to only one U.S. company, or possibly a "foreign" company. Historians mistakenly believe that Duke dominated the early cigarette market, ignoring a more nuanced narrative of how power-including corporations-operated in the expansion of global capitalism. The huge power that Duke ultimately gained came not from technological innovation, but from his ability to compete for control of both corporate management and finance after the founding of American Tobacco. Still, Duke's innovation myth is so convincing that no one has reevaluated this early industry for more than half a century.

Globally, the two entrepreneurs who have made the most significant innovations in Bright Leaf Tobacco Cigarettes are Louis Kinter and Zheng Bozhao. Jinte was the first person to develop mass production technology for bright leaf tobacco cigarettes, and the first person to turn them into American specialty products and launch them to overseas markets. On this basis, he expanded sales to the United States, Europe, Australia and New Zealand, and entered the Asian market. Zheng Bozhao has been working with British American Tobacco's China branch since day one and is the most important entrepreneur in the brand promotion and marketing of Queen's cigarettes. He gave Queen's cigarettes a very important local name-"British Brand". Zheng Bozhao also personally built and firmly controlled the sales system, making the brand popular all over China. Both Kinter and Zheng Bozhao have realized their vision of innovation, not because they are newcomers, nouveau riche or local leaders, but because of their unique business and personal resumes. Jinte's previous experience as an importer and working with men was crucial to cultivating his insights; Zheng Bozhao used his foreign trade experience and connections he accumulated while doing business in Guangdong.

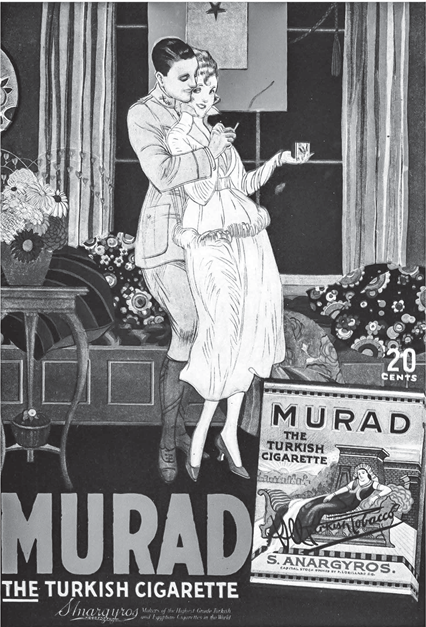

Daying cigarette advertisement

However, to understand the process of innovation, in addition to seeing the contributions of outstanding individuals, we need to look at other entrepreneurs, cultural media, major geopolitical events, and the social flow of the goods themselves. Egyptian, Greek and Jewish merchants had a profound influence on Kinter and American Tobacco and must therefore be considered. In addition, a range of cultural media, including London Club members, famous prostitutes in China, African-American jazz musicians and anti-imperialist revolutionaries in China, have shaped the Bright Leaf Tobacco cigarette market and the cigarettes themselves. Specific geopolitical events, such as the British occupation of Egypt and protests against the U.S. Chinese Exclusion Act, have also left a permanent mark on cigarettes and their brands. Even the cigarette itself is not a blank sheet of paper. Because cigarettes are highly malleable brands, once they are associated with other things, it is difficult to get rid of their shadow. Therefore, the discussion in this book does not simply replace Duke with Jin Te or Zheng Bozhao, but uses a new way to study innovation.

Reflecting expansion

Lee Parker once said that his job is to "put a cigarette in the mouth of every China man and woman," a phrase that is exactly the same as the motif of modernity. He portrays himself as a Western agent taking the initiative and bringing modern goods to passive China; China consumers seem to only have to open their mouths to get cigarettes. The myth of modernity is a narrative with the following core characteristics: it uses technology as a catalytic force; it is characterized by the spread of developed industries, forms of capitalism, and commodities from west to east; it assumes that there is a time lag between development in the West and other countries; and it attributes actions and capabilities to the West and passive acceptance to the East. This is how American historians tell the history of cigarettes. They emphasized the role of cigarette machine technology and praised Duke for successfully opening up an industry in the United States, expanding the national market, and promoting it around the world. We take this motif of modernity for granted too much. This narrative sounds like common sense, but it is actually seriously inaccurate. However, this narrative is repeated only because Parker's memoirs fit the narrative of Western capitalism's expansion, even if his personal wisdom and experience contradict it on several key points.

One thing Parker definitely knew but didn't mention was that when he traveled to China, Turkish tobacco cigarettes were mainstream cigarettes in the United States. In fact, the cigarette industry flows in both directions: Turkish tobacco cigarettes became famous and flowed from east to west, while Bright Leaf Tobacco flowed from west to east. This was common sense in the United States at that time. Throughout their tobacco careers, Ginter and Duke have been trying to shake the dominance of Turkish tobacco cigarettes in the United States.

Parker also did not disclose his full experience at British American Tobacco. This inconsistency emerged in an interview in the 1970s, when the China historian who interviewed him wanted to know how British American Tobacco opened up the China cigarette market. They asked Parker, but Parker didn't know. "This question always embarrassed me," he said."China people know where the market is and how to sell it. I'm just doing superficial work." According to him, British American Tobacco's China employees seem to be proactive agents, while Parker passively "does superficial work." It should be pointed out that similarly, China consumers are by no means passive. Their attitude towards Anglo-American cigarettes was to boycott rather than favor them. They organized such a movement in 1905 and another in 1925. It can be seen that these myths of modernity seem to make people turn a deaf ear to and ignore a large number of interesting facts.

However, we cannot completely abandon the concept of modernity, precisely because modernity not only shapes the way Parker and his colleagues think about their own actions, but also the way they act. They clearly distinguished modern and primitive in their minds. They accepted the imperial privilege of opening treaty ports and regarded themselves as an added benefit of modernity, including employing China domestic helpers and sex workers. Their assumptions about the original nature of China shaped all their relationships with the China and became the basis of British American Tobacco's foreign corporate culture. Compared with the "primitive" of China, they are accustomed to seeing themselves as "modern". Whether in letters, memoirs or interviews, these people in the Bright Leaf Network have never mentioned that their motherland is actually in the process of "modernizing" the tobacco industry, even if they know it well.

Foreign employees at British American Tobacco also believe that cigarettes are fully capable of modernizing China. They package and market cigarettes into modern Western goods, providing a way for cigarettes to be integrated into China culture. Whether in the United States or China, cigarettes are closely linked to another globally circulated commodity associated with the West and modernity: jazz. China still uses the concept of modernity and strives to practice it in cultural, economic and political movements, and has changed the concept accordingly. As a powerful conception of global economic and cultural change, the concept of modernity affects this narrative all the time.

The rise of new cigarette machine technology, empowered companies and the American corporate empire is indeed significant progress, but the cult of entrepreneurship and superstition about the theme of modernity have prevented a reassessment of the nature of this power. Bright Leaf relationships as part of a multinational corporate empire are the key to a new narrative. To reveal this, we need to learn more about Parker and his colleagues rather than just relying on what they deliberately reveal.

The origin of the Bright Leaf Network

White men on the Bright Leaf Network like to say that they "understand tobacco." This is meaningful. What they want to say is that they grew up in areas where bright leaf tobacco is grown in North Carolina or Virginia and are familiar with the requirements for growing and curing bright leaf tobacco. What they are trying to say is that they know how to grade tobacco, how to sell it at auction, and how to make it into pipe cigarettes, chewing cigarettes or cigarettes. They also want to say that they share a common cultural background with others who understand cigarettes, although their opinions or opinions are not exactly the same. They understand that there are many African-Americans who understand tobacco because they are good at selling agricultural products, but those white men also understand that in the growing bright leaf tobacco industry, white-collar jobs are reserved for white people, and this exclusivity has become part of bright leaf tobacco culture.

The Bright Leaf Network is a corporate network composed of white people who understand tobacco. Black people are excluded, and its origins are related to the racial struggle. This network employs employees but also seeks to expand: whether it is expanding in the United States or expanding globally, British American Tobacco provides channels for distribution of manpower, knowledge, seeds, tobacco, cigarettes, etc. Whether before and after corporatization, the Bright Leaf network has expanded. Bright leaves emerged as a particularly profitable emerging agricultural product before the Civil War disrupted the southern economy. Liangye's post-war revival suggests that its planting and manufacturing industries developed during the reconstruction period. Subsequently, the industry reorganized and merged as apartheid began to spread in the United States. The Bright Leaf Network has also gradually developed into a way to inject racial hierarchies into the new social and economic structures brought about by the expansion of capitalism.

From the perspective of African-Americans after the Civil War, bright leaves provide them with huge opportunities to join the upper class. There are three things about bright leaf tobacco itself that are related to its development. First, on the eve of the Civil War, bright leaves were planted in only three counties on the border between North Carolina and Virginia: Halifax and Pittsylvania in Virginia, and Caswell in North Carolina. Secondly, it is very profitable when made into pipe cigarettes because the smoke produced by this cigarette is relatively soft and has an attractive golden color. Because the soil in which it grows is not suitable for the growth of other crops, large-scale planting heralds a sharp rise in land prices and unlimited future profits. Finally, bright leaves are not easy to grow. If you want to grow suitable tobacco leaves, only seeds are not enough. Sandy soil and careful cultivation are also needed. After that, a special method of hot roasting is needed. This process is very technical, so some people call it an art. African-Americans had every reason to believe that the rapid spread of bright leaves after the Civil War would benefit them because under slavery they contracted all the technical and rough work. They know bright leaf tobacco better than anyone else.

Instead, white people controlled fledgling postwar industries, ensuring that new white-collar jobs such as manufacturing, seed development, tobacco grading and sales, and consulting belonged only to white people. This is a long and bloody process that begins with land grabbing and a struggle against the labor system. The timing of violence is seasonal, often occurring at the time when black labor is most needed during the bright leaf baking process. There are also many big events related to the bright leaf industry. In 1870, the Ku Klux Klan assassinated Republican Senator John Stephens, a buyer of bright leaf tobacco, in Carswell County, and blacks fought fiercely for the rights to sell their own tobacco. In 1883, a riot in Danville, Virginia, crushed an interracial political alliance that threatened to retain black labor in the bright leaf tobacco industry to consolidate its power. Finally, as in the southern states, local blacks and lower-class whites fell into a sharing system, which meant that few people could make enough money to buy even a small piece of land.

In the early years, it was enough to start a business with a little resources. Consider the white-collar promotion channels for James Duke, R.J. Reynolds and other tobacco barons: Their family businesses started after the Civil War, when small farms required little capital. As soon as they cultivated bright leaves, they made their own chewing cigarettes and pipe cigarettes on the spot, and then used horses and trucks to sell their products in the south. Some seized the opportunity and quickly built larger production facilities and purchased tobacco from local farmers and tenant farmers. By the 1880s, hundreds of small and medium-sized manufacturers were distributed like grids along the Bright Leaf industrial belt, all of whom were white-owned, and Bright Leaf's profits continued to rise. 3 The monopoly of this industry by white people is not taken for granted, nor is it an accident.

In the 1880s, a large number of reports on early blacks emerged in newspapers and other media in the southern United States, claiming that they did not understand technology, were untrustworthy without supervision, and lacked the judgment needed for management. In other words, this statement denies what is recognized by locals-blacks are highly skilled in shining leaves, and denies that they can be qualified for those white-collar positions in a racial sense. For example, in 1866, the Pittsylvania Tribune published an article about Abisha Slade and his brothers from Carswell County, a well-known early promoter of bright leaf baking techniques. However, the narrative points the pen to one of their slaves, Stephen, who is said to have been interviewed at a tobacco auction in Danville, Virginia. Stephen, who was already elderly, claimed in an interview that he had invented the method of baking, but he didn't discover it while slowly baking it with a stream of hot air. Instead, he fell asleep while working one day and the fire went out. He had to fan the fire and discover the secret of baking. He also expressed his respect for the Democratic Party and his nostalgia for the simple years of slavery. He said: "I wish he (Abisa) were still alive today and I was still his slave." Southern newspapers are filled with fabricated stories that conceal the fact that blacks are skilled in tobacco, while simultaneously portraying blacks as simplistic, reflecting how modern, fashionable and technologically savvy whites are. In this way, these stories connect apartheid, which originated in local conflicts, with the internationally circulated rhetoric of civilization and barbaric imperialism.

American Tobacco Company Advertising

Bright leaf networks and corporate imperialism

After corporatization, American Tobacco took over the Bright Leaf Chewing Tobacco and Pipe Tobacco Company strongly, and transformed the white-collar workers in the Bright Leaf industry into the backbone of the Bright Leaf network. As a product and expression of apartheid, the Bright Leaf Network provided an environment that mimicked the hierarchical system of apartheid as the company expanded. Over the next two decades, American Tobacco continued to expand domestically, with former factory owners and managers working in emerging companies, some at its New York headquarters and others in its rapidly expanding overseas industries.

Relying on its basic market in the British Commonwealth, American Tobacco first acquired companies in Australia and Canada. Later, as the United States grew, American Tobacco Company's ambitions gradually expanded, especially focusing on the markets of East Asia and Southeast Asia. In 1887, the United States gained control of Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and Pago Pago in Samoa. In the 1898 war, the United States occupied the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Guam and temporarily controlled Cuba. That same year, the United States forcibly occupied Hawaii. The company is a key institution for the United States to grow its imperialist power; in turn, companies like American Tobacco can benefit from the privileges generated by war and strong foreign policies. When the United States occupied the Philippines, the American Tobacco Company sent James A. Thomas. Thomas) went to Manila to sell tobacco to the U.S. military. In 1899, American Tobacco took control of the Murai Brothers Tobacco Company of Kyoto in Kyoto, Japan, and it later became a major production center for American Tobacco, used to expand sales of bright leaf cigarettes in East Asian ports.

In 1902, American Tobacco continued to expand in a new way. Over the past decade, it has acquired existing tobacco companies overseas, using them as a basis for developing new markets. American Tobacco and Imperial Tobacco merged to form British American Tobacco, a move that merged the world's two largest Bright Leaf giants into one company, specializing in overseas expansion missions. The merger also allowed the company to tap into the power and vast infrastructure resources of the British Empire. In an interview with a British tobacco industry magazine, Duke praised the establishment of British American Tobacco generously: "England and the United States should work together in big companies rather than compete with each other. No matter how you look at it, isn't this a big deal? Together with me, we will conquer the world." Neither British American Tobacco nor the British and American governments have established special ties, but they themselves support imperialism.

The connection between business and imperialism was not new during this period, but it was changing. Joint-stock companies emerged in the 16th century, and these imperial chartered joint-stock companies were like the right arms of enterprises. The British East India Company, the Dutch East India Company, the Hudson Bay Company and many other companies were used to seize resources and develop markets in colonial outposts. As an early method of colonization, many of these companies had both economic and political functions. The British government only withdrew the licence of the British East India Company and imposed monarchical rule on India in 1857, the year when the company's tyranny triggered the uprising. For a variety of reasons, these companies may or have been granted concessions on many land, including building schools, churches, public services and other projects. However, the three hundred years of history of the imperial enterprise did not end, as it laid the foundation for the development of new relationships between "private" commercial companies and the imperial authorities. Multinational companies like British American Tobacco or American Tobacco were not explicitly chartered as colonial institutions by a single government, but acquired this qualification through the process of establishing connections with multiple imperialist institutions and created unequal economic and political power.

British American Tobacco's large-scale expansion in China is a new departure for Bright Leaf. British American Tobacco's predecessor has been selling cigarettes to China for more than ten years, but the decision to establish a factory in 1905 was undoubtedly an important starting point for the company. As long as the Murai Brothers Tobacco Company acquired by British American Tobacco can produce British American Tobacco's products exported in East Asia, the company can manage sales in China only through China's commission agents. However, in 1904, Japan nationalized the Murai Brothers Tobacco Company. British American Tobacco lost its outpost in Japan and turned its sights to China. This time, British American Tobacco was not able to take over the already successful local tobacco companies as in other regions, so it didn't take long for the company to establish a comprehensive production center in China, covering the entire process from bright leaf planting to making and packaging cigarettes. The company sent dozens of foreign managers instead of a few. In the end, hundreds of foreign representatives embarked on the journey.

In China, British American Tobacco says it has benefited from half a century of imperial wars and diplomatic pressure from Britain, Germany, the United States, France and Japan. The Opium War ended with the signing of a series of treaties, forcing China to open multiple treaty ports and grant many privileges to British companies. European and American countries and later Japan all demanded the same privileges. Importantly, these privileges include extraterritorial jurisdiction, which means that foreigners are only subject to the supervision of their own police and judicial systems in the concession, rather than the jurisdiction of official China agencies. Extraterritorial jurisdiction denies the China government's jurisdiction on their own land, which European countries take for granted. In 1895, Japan defeated China during the Sino-Japanese War of 1895 and won several new rights for foreign companies, including the right to own real estate and the right to invest and set up factories in treaty ports. At the turn of the century, foreign companies such as British American Tobacco expanded their operations to Shanghai because the right to build factories was guaranteed.

By 1918, more than 7000 foreign companies had their headquarters in Shanghai, and in order to cater to foreigners, Shanghai gradually developed an elaborate imperialist leisure culture. Foreign employees of British American Tobacco enjoy these privileges and services tailored for them. It has a large number of cheap servants and bustling entertainment venues, including fine clubs, restaurants, racetracks and cabarets. Shanghai's concession and commercial district, known as the Bund, are developing at a breakneck pace, while the construction of European-style office buildings and houses has forced large numbers of China people to go to "China City." For British American Tobacco's foreign representatives, the experience of apartheid immediately made Shanghai's environment feel unique and familiar. As Lee Parker later recalled,"It was great for young Americans, because during the extraterritorial era, we lived in a small community, and you might call it apartheid."

It is clear that apartheid, corporations and imperialism are forming a new relationship, but how the situation between China and the United States will develop is by no means predetermined. Corporate empires are powerful, but they cannot do whatever they want. The value of a commodity depends on the labor, support and thinking of the land and thousands of people. Many people together form the skeleton of the company and leave their own mark, but at the same time, there are also some people who are waiting for opportunities to destroy and win over. Employees and consumers use cigarettes and brands in unexpected places. Zheng Bozhao gradually gained enough rights from British American Tobacco to make decisions on major matters and force foreigners in British American Tobacco to adapt to the operation of China's national capitalism, which was formed under their guidance. In other words, tobacco companies of all stripes are large and chaotic organizations that are always in the process of change.

(This article is excerpted from Nan Enstad's "Cigarette Co., Ltd.: A Study of Sino-US Tobacco Trade 1870-1930", translated by Wang Jing, Xinxing Press, August 2024. The Paper News is authorized to be released, with the original annotations omitted, and the current title is prepared by the editor.)